Gochugaru Girl recently spent a morning being troubled by one recurring question.

If it is difficult to enter China with a valid passport, how much more difficult would it be to enter if you did not have a passport?

If it is difficult to enter China with a valid passport, how much more difficult would it be to enter if you did not have a passport?

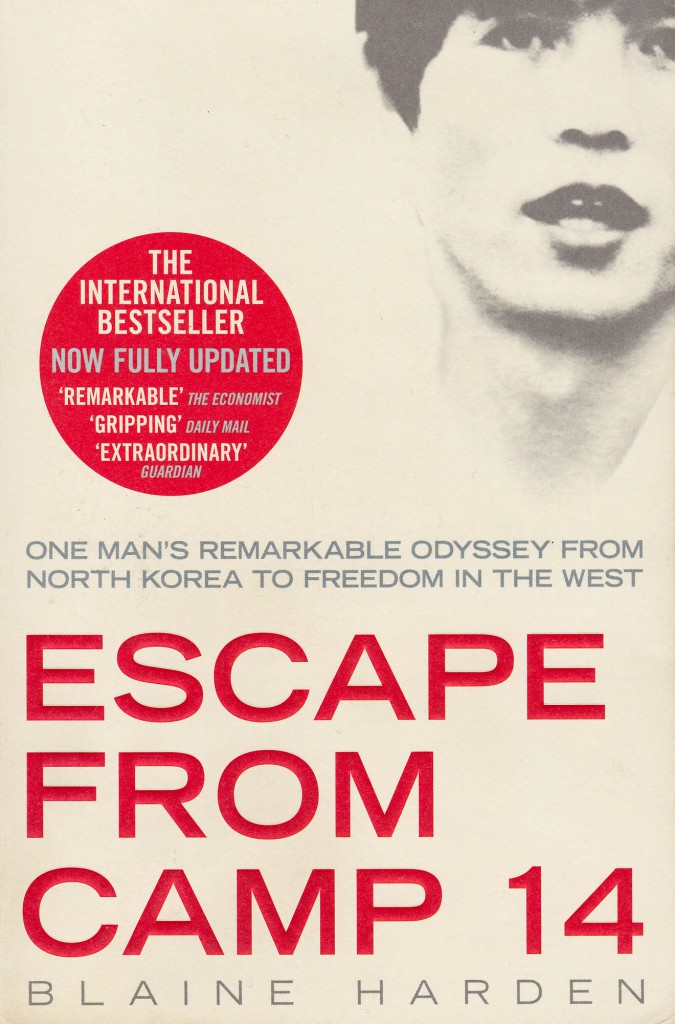

This is a continuation of earlier posts introducing the book Escape from Camp 14 and the official reason for Shin Gong-hyuk’s incarceration in a political camp.

One of my favourite narratives from the Bible is the Old Testament account in the book of Exodus, of God leading the Israelites out of Egypt. They and their ancestors had been slaves for a large part of the 430 years spent in that country. There is quite a lead up to the eventual departure, as there is in Shin’s story.

The main difference is that with the Israelites’ flight out of Egypt, God intervened and was credited right from the beginning with the rescue plan. With Shin’s escape from North Korea, he could only trust himself and his fellow prisoner Park Yong Chul. The consequences of being caught even having such a conversation would have been fatal to both men.

Self-reliance meant that “their plan was simple – and insanely optimistic. Shin knew the camp. Park knew the world. Shin would get them over the fence. Park would lead them to China, where his uncle would give them shelter, money and assistance in travelling on to South Korea.” [1]

In the event, Park did not get out alive. After escaping the camp, Shin was left to find his own way towards the Chinese border with no money, no passport, no guide and no knowledge of a life outside what he had known in the prison camp.

This thought struck me as I spent a frustrating morning applying for a visa for an impending trip to Shanghai. I had with me every document required and yet, when I presented all my papers, the officer managed to find fault with the application.

Returning to the situation facing Shin, I marvelled that he not only managed to get into China but then survived – first by taking on farm jobs and then by moving from place to place to look for menial work, and for help to reach South Korea. This went on for over a year. On the final stretch he travelled to Beijing, Tianjin, Jinan, Hangzhou and Shanghai.

In Shanghai, Shin once again searched for work in Korean restaurants. At the first establishment he approached, the waitress pointed Shin to a man at another table. This turned out to be a Shanghai-based journalist from South Korea.

It was at this point in the story that I realised my engagement with this book had so far been slightly detached. I could not see how Shin would meet a person who could make a difference to his life. It was as if, in reading the account of Shin’s emotional fear, where he did not understand what hope was, my own senses had been numbed as well.

Now my heart beat a bit faster, because when the rescue came it was very quick and very dramatic. On that very same day, the journalist bundled Shin into a taxi and the two men went immediately to the South Korean Consulate. This was heavily guarded by Chinese police, who had a duty to stop North Koreans seeking asylum at foreign embassies and consulates.

“When the taxi stopped in front of a building flying the South Korean flag, Shin’s chest felt heavy. Out on the street, he feared he would not be able to walk. The journalist told him to smile and put his arm round Shin, pulling him close to his body. Together they walked towards the consulate gate. Speaking in Chinese, the journalist told police that he and his friend had business inside.” [2]

The rest of the book documents Shin’s new life, and makes for a fascinating read. My personal view is that this journey from slavery to freedom would not have been possible without the unseen hand of God intervening. Shin believes as much [3]:

In California, Shin began giving God all the credit for his escape from Camp 14 and his good fortune in finding a way out of North Korea and China.”

This was not without its difficulties: “His emerging Christian faith, though, did not square with the timeline of his life. He did not hear about God until it was too late for his mother, his brother and Park. He doubted, too, that God had protected his father from the vengeance of the guards.” [4]

Earlier, I mentioned that the first question in Christianity Explored is this: “If you could ask God one question, and you knew it would be answered, what would it be?”

God’s fairness plagues people’s minds, and rightly so. Why did Shin escape whilst other prisoners remain in North Korea? Does God care for some people and not others? I too, have these questions. and can only declare what I believe: that God is fair and just, that we do not necessarily understand everything that happens in our lives, that there is a day of judgement and I can be assured that there is no evil act that will go unpunished.

One final thought: at the end of the day, like the Israelites in Egypt, like Shin in North Korea, we are all slaves. Perhaps not in a physical sense, but we are slaves to something: money, relationships, work, beauty, lifestyles. Left to our own plans, we will not be able to escape this kind of bondage. It takes a helping hand from God to be led to freedom and it takes faith and trust on our part to want to accept this new life.

* Escape from Camp 14: One man’s remarkable odyssey from North Korea to freedom in the West by Blaine Harden, published by Pan, ISBN 978-0330519540.

All references are from the book:

[1] page 127

[2] page 182

[3] and [4] page 212

An interview by the Financial Times with Shin Dong-hyuk: http://www.ft.com/cms/s/2/1505c16a-0ff2-11e3-99e0-00144feabdc0.html#axzz3DoCyZXtp